OXtal: Generative Molecular Crystal Structure Prediction

In 1988, the editor of Nature, John Maddox, famously declared, “One of the continuing scandals in the physical sciences is that it remains in general impossible to predict the structure of even the simplest crystalline solids from a knowledge of their chemical composition.” [1]

He was right – if we know the atoms in a molecule, why can’t we predict how they will pack in a solid? Nearly forty years later, this problem of Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) remains one of the grand challenges in computational chemistry.

Today, we share OXtal, an all-atom diffusion model that shifts how we approach predicting molecular crystal structures. Developed through a collaboration between Caltech, Oxford, Mila, AITHYRA, and other institutions, OXtal predicts experimentally realizable crystal packings directly from 2D molecular graphs, replacing thousands of CPU hours of physics simulations with mere seconds of generative modelling.

The "Ghosts" of Chemistry

To understand why this problem has persisted for forty years, one must first appreciate the intricate energy landscape of molecular crystallization.

Unlike proteins, which are constrained by strong internal backbones from only a few dozen amino acid types, or inorganic crystals (like salt or silicon) that are held together by stiff ionic or covalent bonds, molecular crystals have significantly more diversity and are held together by the "ghosts" of chemistry: weak, fleeting Van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions.

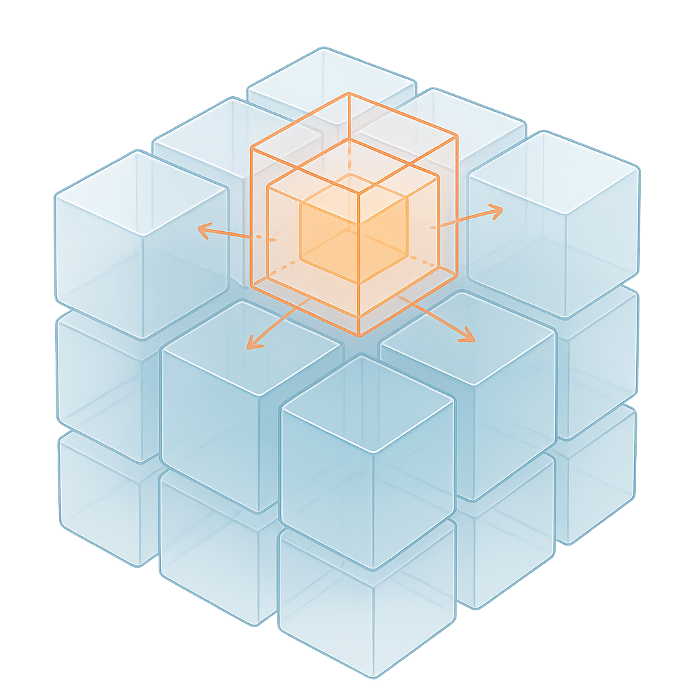

These forces dictate the formation of the crystal lattice. In a crystal, molecules don’t just pile up randomly; they arrange themselves into a precise, infinite periodic grid defined by a “unit cell,” the smallest box that repeats in all directions.

Because forces in the lattice are so delicate, a tiny shift in energy, less than the thermal fluctuations at room temperature, can cause a molecule to pack into completely different 3D arrangements called “polymorphs”. This can significantly change a material's properties, such as its solubility, charge mobility, mechanical strength, or optical response. For a pharmaceutical company, a surprise polymorph can mean the difference between a life-saving pill and a brick of powder that doesn’t dissolve in the body.[2] For organic semiconductors, it can mean the difference between a high-performance, flexible transistor and a piece of plastic that conducts no electricity at all.[3]

The theoretical foundation for predicting these interactions lies in the Schrödinger equation. However, solving this equation exactly is computationally intractable for complex systems. For decades, the field has bypassed this impossibility by relying on Density Functional Theory (DFT) to approximate these energies.[4] More precisely, the gold standard approach involves running search algorithms using DFT to brute-force “shake” atoms around until they settle into some energy minima.

While this approach works, the cost is prohibitive. In the most recent 7th CSP Blind Test, predicting just seven target crystals[5] consumed a staggering total of 46 million CPU core hours (roughly $4M USD).[6] This unscalable cost makes it impossible to "search" our way through the millions of possible drug candidates or materials.

OXtal: A Generative Shift

We therefore ask a simple question: Can this expensive search be replaced with a direct generative process?

OXtal shows that it can be. Unlike search algorithms that traverse an energy landscape, OXtal is an all-atom diffusion model that learns to "denoise" random arrangements of atoms into stable crystal packings. It solves the joint distribution of the molecule's internal conformation (how it bends) and its external packing (how it packs) simultaneously. We've seen it successfully predict distinct polymorphs for the same molecule—capturing not just the single "best" structure, but the thermodynamic diversity that exists in nature.

Scaling with Soft Symmetries

Building an "AlphaFold for Crystals" isn't straightforward. Crystals are infinite periodic systems, and we cannot simply feed a model an infinite lattice. Previous approaches have tried to explicitly force the model to understand the complex mathematical symmetries of crystals, often using equivariant neural network architectures. While mathematically elegant, these models are not always GPU-friendly, making them difficult to scale. With OXtal, we take a somewhat controversial bet: scale beats hard-coded symmetry.

Following inspiration from recent literature[7], we abandon explicit equivariant architectures in favor of massive data augmentation and a new training paradigm we call Stoichiometric Stochastic Shell Sampling (S4).

Instead of predicting the global lattice parameters defined by the "unit cell" box directly, S4 trains the model to understand the local neighborhood—how one molecule likes to sit next to another.[8] By accurately solving the local packing puzzle, the global periodic structure naturally emerges. This allows us to train a 100M parameter model on 600,000 experimentally resolved structures.

Fast and Furious

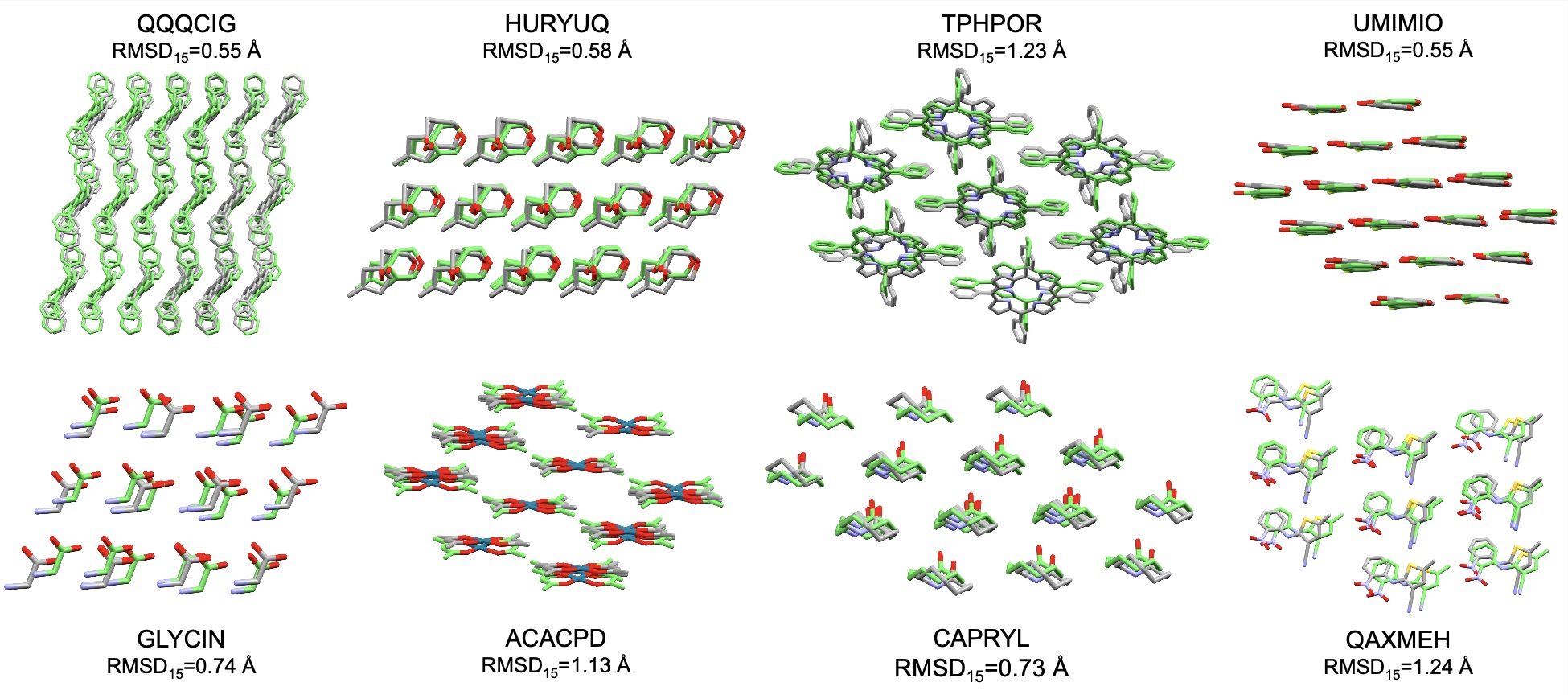

OXtal achieves orders-of-magnitude improvements over previous state-of-the-art machine learning methods[9] and changes the economics of discovery.

Traditional DFT methods may take days to weeks of running on large CPU clusters to screen a single molecule. OXtal can generate accurate candidate structures (RMSD₁₅<0.2nm) in seconds on a single GPU. In the context of the historic CSP Blind Tests, OXtal’s inference cost is essentially a rounding error.

A Step Forward, Not a Closed Caseload

We want to be clear: CSP is not "solved" yet.

OXtal is a step towards efficient screening, allowing researchers to screen thousands of compounds rather than a handful. However, while OXtal is an efficient sampler, it cannot currently rank polymorphs by free energy, nor does it fully capture kinetic conditions. Our solve rate, sample efficiency, and packing diversity also have plenty of room for improvement.

Nevertheless, OXtal can be used to easily model thousands of crystals, and we hope it can be used as a high-throughput filter that sits upstream of traditional, expensive physics-based validation, further scaling molecular crystal design.

Interested in the details? Find the preprint here: http://arxiv.org/abs/2512.06987

Code and a Google Colab will be released soon.

[1] Maddox, J. Crystals from first principles. Nature 335, 201 (1988).

[2] A classic example is Ritonavir, an antiretroviral medication. After it was marketed, a new, more stable (but less soluble) polymorph appeared, compromising the drug's bioavailability and forced a global recall and reformulation.

[3] In organic semiconductors, charge mobility is heavily dependent on molecular stacking. A slight variation in crystal packing can reduce charge carrier mobility by orders of magnitude, rendering the device (transistors, photovoltaics, OLED, etc.) inefficient.

[4] Exact solutions to the Schrödinger equation for many-body systems are impossible to calculate efficiently. DFT reformulates the problem in terms of the electron density rather than the wave function of every individual electron. With the exact exchange–correlation functional, DFT would reproduce the exact ground-state energy, but in practice only approximate functionals are available. This framework, for which Walter Kohn and John Pople were awarded the 1998 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, makes quantum mechanical calculations feasible, though still computationally heavy for large searches.

[5] Although there are 7 crystal targets, one co-crystal contains polymorphs with two different stoichiometries. Therefore, there are technically 8 crystal structures in total.

[6] This is calculated based on AWS on-demand pricing for c5.large at us-east-1, which is priced at $0.085/hr. Spot pricing, which is currently $0.045/hr, would be ~$2M USD.

[7] Wang Y., Elhag A. A., et al., Swallowing the Bitter Pill: Simplified Scalable Conformer Generation. ICML 2024; Abramson, Josh, et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493 (2024)

[8] Very roughly, S4 samples successive “shells” of neighboring molecules around a reference molecule while enforcing the overall stoichiometry of the crystal. During training, the model sees many randomly oriented local neighborhoods of varying sizes, which encourages it to learn repeating interactions without explicitly encoding full space-group symmetry.

[9] Here, we specifically refer to ab initio ML methods without any geometric inductive biases or optimization. There are recent ML-based methods like FastCSP which combine search methods with an ML-based energy function. OXtal, on the other hand, does not require any energy function and directly reproduces the underlying thermodynamic and kinetic regularities by learning from data.